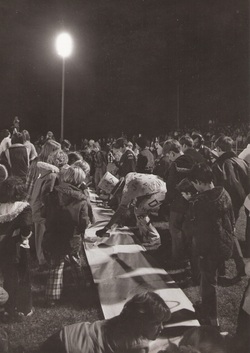

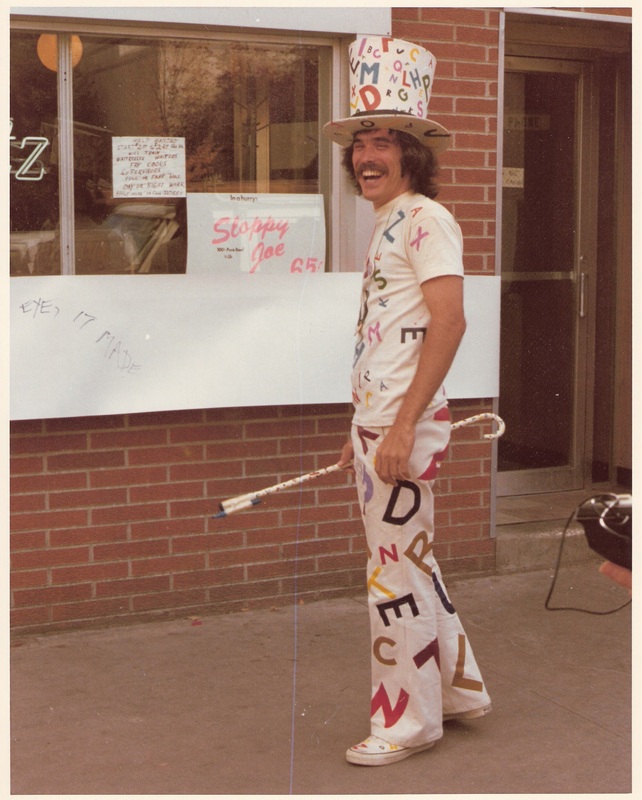

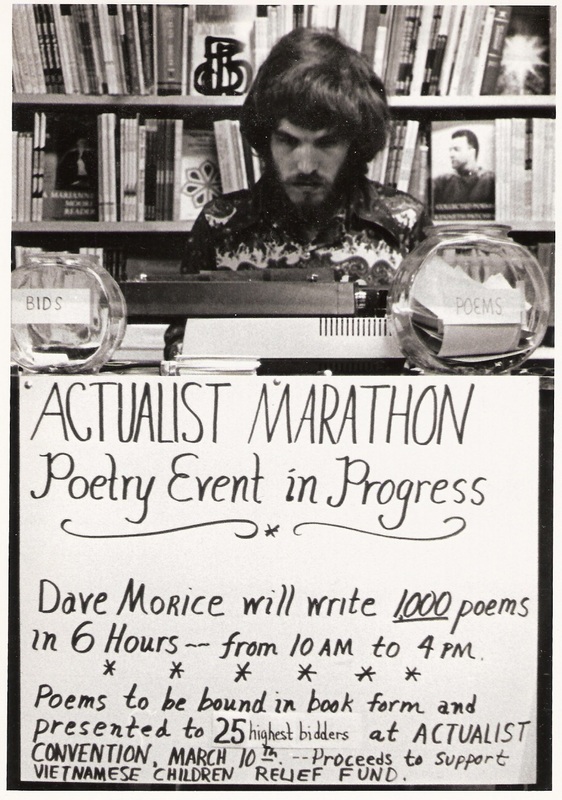

| Dave Morice is a writer, visual artist, performance artist, and educator whose books include 60 Poetry Marathons, three anthologies of Poetry Comics, How To Make Poetry Comics, The Adventures of Dr. Alphabet: 104 Unusual Ways To Write Poetry in the Classroom & the Community, and The Great American Fortune Cookie Novel. His visual art projects include Rubber Stamp American Gothic and The Wooden Nickel Art Project. Morice and I talked about his influences, his poetry projects, and writing 10,000 pages of poetry in 100 days. DG: How did you first get interested in writing? DM: When I was 6 years old, I wrote poems in rhymed couplets about "Why the GIraffe Has Spots," "Why the Zebra Has Stripes," and others, and I drew pictures of the animals to go with them. I would give them to my mother, and she would praise them, saying "You're going to do great things someday." DG: Who are some of your influences? DM: William Carlos Williams, Dylan Thomas, Gertrude Stein, T.S. Eliot, Anne Knish, Emanuel Morgan, James Joyce, Something Else Press, Anselm Hollo, John Knoepfle, Al Montesi, Ron Padgett, Ted Berrigan, Frank O'Hara, John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, Syvia Plath, and the Actualists. Those are just a few that come to mind right now. E.E. Cummings. Dick Higgins. There are more. John Cage. Joyce Holland. Joyce Kilmer. I am easily influenced. William Shakespeare. DG: How did you first get the idea to create poetry comics? DM: I was dating a girl in the Workshop who had a dozen black binders full of poems on her desk. I had about the same amount of the same binders at my place. They don't make those binders anymore. Anyway, I went over to her place, and we started talking about poetry. Her voice was very serious and workshoppy that night, and at one point she said, "Great poems should paint pictures in the mind." I thought about it for a minute, and then I decided to go in the opposite direction. I said, "Great poems would make great cartoons." She hesitated a moment, and then she laughed and said, "Hey, you know you're right. You ought to do some." And what began as a smart alec answer turned into a major fun project. The following week I taught a poetry workshop in a junior high in Oskaloosa, Iowa. By day I talked poetry, by night I drew a cartoon version of "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock." Football Poem DG: How would you say your poetry comics concept has evolved over the years? DM: It evolved in several ways. To begin with, I thought I was doing something very underground that would shock the academics. Then I heard some teachers, including one at the UI English Department, used Poetry Comics as a teaching device. As a Writers-in-the-Schools teacher, I used it in classes, too, and I still do. Second, when I first began putting out the magazine, I thought it would work only with famous classical poets. DG: How did you decide to create poetry comics based on works by your contemporaries? DM: Some people wrote to me and asked why I didn't do contemporaries, so I put out a Contemporary Poets issue that included Creeley, Ashbery, and Ginsberg. Readers liked that. Of course, those three poets are well-known, well-established pillars of contemporary verse. Soon I put out issues with the good old gang of unknowns like me. I also included the classical poets. DG: How did that lead to book-length publications of "Poetry Comics"? DM: The Village Voice did a wonderful article about the magazine, and Simon & Schuster wrote to ask if they could publish an anthology. Well, after two seconds of hard thinking, I said yes. I had hoped it would find its way into schools around the country. Teachers & Writers published "How to Make Poetry Comics" to accompany the anthology. I had been trying out different ways to use poetry comics in the classroom, and this manual gave me a chance to organize this approach. Eight years later, a Chicago Review Press editor contacted me. He said he used to teach poetry in high school, and he used Poetry Comics. He wanted me to do a second anthology. About six years after that, Teachers & Writers did a third anthology, which included classroom exercises in the appendix. Over the past 6 or 7 years, other people have been using the idea of poetry comics in the classroom.Teachers & Writers Magazine published a special issue called "Comics in the Classroom." Now it is a perfectly acceptable way to teach poetry writing. For me, the main way that the poetry comics idea has evolved is the discovery that different poems demand different styles. "The Raven" by Poe wouldn't work using funny animal characters; instead I made the Raven into a supervillain character dressed as Batman. DG: How did you first get the idea to do some of the projects that you describe in “The Adventures of Dr. Alphabet”? DM: I had done several poetry marthons and other public writings, starting in 1973. Barry Nickelsberg of the Iowa Arts Council heard about them, and he asked if I would like to try teaching a senior citizen poetry class, and I was happy to do so. I had lived with my grandmother and grandfather for a few years, and I had a lot of respect for old people. I started the class by giving topics for the students to write about. I also used Kenneth Koch's Wishes, Lies, and Dreams a couple of times, but before too long, I wanted to make up my own exercises. The first one was "Poetry Poker." DG: What is "Poetry Poker"? DM: It uses used poker cards with random phrases typed on them. I dealt the students a five-card hand and asked them to write poems using all the phrases and combine them with words of their own. That has been remained one of the best "ice-breaker" activities that I've ever used. | Dave Morice -- during "Poem Wrapping City Block" DG: What are some other activities you developed early on, which were later included in "The Adventures of Dr. Alphabet"? DM: I built a "Poetry Castle" out of a cardboard box, and the senior citizens cut out phrases from magazines and glued them to the castle, and then they wrote poems based on the phrases (similar to the "Poetry Poker" idea). The next step led to a big breakthrough: The exercises moved from writing on paper to writing on all kinds of things -- a chair, lamps, mirrors, and so on. I would go to stores and look at the objects and try to figure out which would make a good, unusual writing surface. After a year or so with the senior citizen class (which continued for 10 years), I started teaching at schools around Iowa through the Iowa Arts Council, and I used ideas from the senior citizens class as well as new ideas. DG: What are some other unusual poetry projects that you've developed? DM: We did a project inspired by the poetry marathons, where students and I wrapped their school in a long sheet of paper, and then we would write and/or draw on it. This project usually concluded a five-day WITS program. One thing about both the seniors class and the school classes is that I often tried new approaches and new materials. I don't think of the projects as just school assignments; I consider them to be multimedia artworks in their own right. DG: How did you come up with the idea for "The Great American Fortune Cookie Novel"? DM: Like many people, I save fortune cookie fortunes as I get them. I had about 90 sitting in a box on a shelf, and one night I picked them out of the box and read them. I wondered if I could make a poem by stringing a few of them together. It was very easy to do so. The results sounded serious, as if a philosopher were giving out gems of knowledge. Then I wondered whether I could write a novel using fortunes, which turned out to be a real challenge. I told a reporter at The Cedar Rapids Gazette about the idea. She was a big fortune cookie fan, and she wrote a column about this project, concluding with an invitation to send fortunes to me for inclusion in the novel. In return the donor would be listed as a co-author. DG: How did you develop "The Great American Fortune Cookie Novel," in that collaborative spirit? DM: I received many fortunes from readers, friends, and friends of friends. Still, I needed a lot more. I bought cases of fortune cookies from stores in town and elsewhere. I kept track of them on my computer. One fortune that I found suggested a plot: "Help! I am being held prisoner in a Chinese bakery." I divided the book into 12 chapters, one for each animal in the Chinese Zodiac. "Year of the Dragon" began the book. I bought stamp albums that had strips of plastic forming long pockets across the page -- perfect for storing the fortunes. When the book finally came out, there were over 500 co-authors, and at least two of them have listed their co-authorship on their résumés. Dave Morice & the Actualist Marathon DG: How did you get involved with the "10,000 poems in 100 days" exhibit that you did in 2010? DM: Tim Shipe, a bibliographic librarian at the University of Iowa Libraries, contacted me about an exhibit to celebrate the fact that Iowa City has been designated as one of three "Cities of Literature" by UNESCO. The exhibit was divided into two parts -- the Writers Workshop (Poetry and Fiction Workshops, International Writing Program, and Summer Writing Program), and the Actualist Poetry Movement. Tim asked if I could loan the original Dr. Alphabet outfit to the library for the exhibit. DG: How did you propose that the Iowa City Poetry Marathon project be part of the exhibit? DM: When I brought the original Dr. Alphabet outfit to Tim, I asked if I could write a poetry marathon during the exhibit, and he and his committee agreed. It was the biggest marathon by far that I've ever done -- a 10,000-page book in 100 days. It gave me a way of putting the puzzle of my literary life together. The marathon included most of the text of the 60 marathons and other public writing events that I've written -- they have been hiding in the attic for more than 25 years, and they finally saw the light of the printed page. The Iowa City Poetry Marathon website has the text of each of the 100 volumes displayed for people to read on a daily basis, and there were many other things in the marathon. They were linked together by a plot based on my favorite marathon of all, the Poem Wrapping a City Block, which had many other performances going on at the same time. That day was the last day I wrote the original Dr. Alphabet outfit, and the event was titled "Poetry City Marathon." I've written marathons since then, but this was the last that had the excitement of the Actualist Days. In order to get back to Poetry City, I must follow a paper trail of 10,000 pages. |

|

2 Comments

|

AuthorArchives

April 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed